My name is Linda. I write a bi-weekly newsletter about computer science, childhood and culture - and there are 9771 of you listening. If you enjoy this issue, please share it with anyone you think may find it useful.

I’ve been thinking recently a lot about nature, technology and how childhood animism might give us an understanding of that which is considered different than we are. No activities this week, but a few favorite quotes from Sherry Turkle and Edith Cobb. Scroll down!

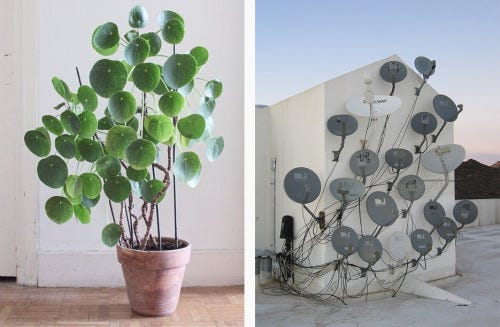

Image by Jill Bliss, discovered through Algorithmic Botany

Young children, who believe in the spirit of the trees, the fairy footprints in the snow and the independent will of a missing sock make us smile.

Childhood animism, the trouble children have differentiating between animate beings, plants, and inanimate objects, is often seen as a pre-operational, developmental phase. But maybe it’s a solution.

Grownups tend to think technology works for us, but this is rarely the case, as we’ve seen with climate change, algorithmic discrimination and other systematic, global problems. Imagination, empathy and wonder are supported as a phase, rather than being appreciated as a fundamental intelligence we could learn from.

Two books I’ve read in recent years that touch on the topic are Edith Cobb’s The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood (1977) and Sherry Turkle’s The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (1984).

“It was Jean Piaget who discovered the child as metaphysician. Beginning in the 1920s, Piaget studied children’s emerging way of understanding such aspects of the world as causality, life, and consciousness. Children begin by understanding the world in terms of what they know best: themselves. Why does the stone roll down the slope? “To get to the bottom,” says the young child, as though the ball had its own desires. “ writes Turkle about how we learn about the world.

In her book, Edith Cobb elaborates on the sensory experience of self and the natural world we experience as children. The sand, twigs and stones we play as kids are, according to her, “world-making” or “world-shaping” activities. She writes about the childhood joy and need to order, name and classify our world, to discover logic in nature and our world. All this as a basis for our adult imagination.

Cobb’s joyous philosophy comes to a clash with the computer and its inherent opacity. We understand a pinecone in terms of its seeds and a bicycle in terms of its pedals, but computers are a mystery.

So what do computers mean for the development of our imagination? From Sherry Turkle: “Childhood animism, this attribution of the properties of life to inanimate objects, is only gradually displaced by new ways of understanding the physical world in terms of physical processes. In time the child learns that the stone falls because of gravity; intentions have nothing to do with it. And so a dichotomy is constructed: physical and psychological properties stand opposed to one another in two great systems. The physical is used to understand things, the psychological to understand people and animals. But the computer is a new kind of object-psychological, yet a thing.”

A new kind of object - physchological, yet a thing. This sentence makes me shiver every time. Maybe the ability to recognise and work alongside human and non-human intelligence, be it in plants, ants or algorithms offers a much more optimistic and life-affirming idea of progress for our interspecies world.

Image by Christine Ödlund, discovered through Server Garden

Linked List

In computer science, a linked list is a linear collection of data elements whose order is not given by their physical placement in memory. But here it is a selection of things I’ve been reading lately.

Heidegger & Ghibli. “Miyazaki’s anime and Heidegger’s later thought share the sense that technology is not merely destructive to nature, but also represents a loss of the gods. If earth is a supply of resources, it can no longer be a site of the sacred. (…) While not adopting a simple Luddite solution, how should we co-exist with nature? This seems to be an open question that Miyazaki and Heidegger pose to us.”

The Silurian Hypothesis. Would it be possible to detect an industrial civilization in the geological record?

“For me, nature and technology stand for hope, and for a movement onwards to the future.” - Björk, always Björk.

Biomimicry in computer science and how nature influences programming.

The classroom

Image from Christoph Rauscher, discovered through Algorithmic Botany

Thank you for the photos of your Internet infrastructure walks - I loved seeing the attention in practice.

Hit reply and answer me:

Where did the computer come from? Tell an (animistic) story.

What are the beliefs children hold about computers we can learn from? What kind of an intelligence is the computer?

How might anthropomorphizing technology or non-human intelligence be harmful?

Inspired by your text. In fact, so much I hit reply to answer your first question.

Once upon a time, in the far-far away land of Londonium, there lived a young boy name Barles Cabbage. He loved numbers, in fact, he loved crunching them. He would crunch them affectionately like you might crunch your morning cereal. Numbers were his friends, so Barles decided to build them a home, a place where they could live and play. It would be a wondrous place, a place to where Barles could always visit his number friends and ask them questions. Because this was what Barles loved – he loved asking his number friends questions. So he went out and built the number home and called it the Difference Engine. Barles also had a human friend, her name was Ada. One day Barles showed Ada the Difference Engine and immediately Ada loved it. She saw the numbers moving around and playing, while she kept on asking them questions. Ada got so excited, she made up games for the numbers that would get them to play one game after the other, repeating them in different orders, and making the numbers move vigorously. Suddenly, much like a dance, she saw that the numbers could answer complex questions, as long as she put a lot of simple questions in the correct order. So inspired by how the numbers would not become tired of their dance, she exclaimed: "One day I will be able to compose music with this! Only the sky is the limit on what I can create with you!”

And so, that is how the computer came about. A home for numbers to move and answer all the questions we can think of asking them.

I've always been frustrated before when children think that the monitor is the computer, but you've made me think about this in another way. For kids the computer seems to be the interaction, or maybe the screen is the face, or perhaps the personhood of a computer.