No. 106 — Proust and the Squid ⫶ Memory and monuments ⫶ Counting spaces

time goes porous

My name is Linda. I write a bi-weekly newsletter about computer science, childhood, and culture.

August holidays brought an unplanned pause. I’ve been mostly off the computer, so just a short list of links this time. La rentrée is around the corner, and regular programming returns soon.

Some selected summer in Finland 2025 recommendations: Söderlångvik manor and Kim Simonsson giant moss statues. Klaava winebar. Helsinki Biennial, if only for Vallisaari. Shii. Naantalin kirjajuhlat. Day screening of Phoenician Scheme. Olafur Eliasson’s Long Daylight Pavilion in Kruunuvuorenranta. The sea, everywhere.

1.

I’ve been wrapped up in Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid, a tour of how reading was invented and how it rewires us. It is neuroscience told with a novelist’s brain.

An example. Wolf walks you through a 233 word Proust passage at speed and explains what happens in our brains:

Let’s go back to what you did when I asked you to switch your attention from this book to Proust’s passage and to read as fast as you could without losing Proust’s meaning. In response to this request, you engaged an array of mental or cognitive processes: attention; memory; and visual, auditory, and linguistic processes. Promptly, your brain’s attentional and executive systems began to plan how to read Proust speedily and still understand it.

Next, your visual system raced into action, swooping quickly across the page, forwarding its gleanings about letter shapes, word forms, and common phrases to linguistic systems awaiting the information. These systems rapidly connected subtly differentiated visual symbols with essential information about the sounds contained in words. Without a single moment of conscious awareness, you applied highly automatic rules about the sounds of letters in the English writing system, and used a great many linguistic processes to do so. This is the essence of what is called the alphabetic principle, and it depends on your brain’s uncanny ability to learn to connect and integrate at rapid-fire speeds what it sees and what it hears to what it knows.

Then, after you integrated all this visual, conceptual, and linguistic information with your background knowledge and inferences, you arrived at an understanding of what Proust was describing: a glorious day in childhood made timeless through the “divine pleasure” that is reading!

That’s the everyday miracle of reading. I knew all of this, but still the wonder of it had been lost on me.

Now for the part that made me grin:

Years ago, the cognitive scientist David Swinney helped uncover the fact that when we read a simple word like “bug,” we activate not only the more common meaning (a crawling, six-legged creature), but also the bug’s less frequent associations—spies, Volkswagens, and glitches in software.

Swinney discovered that the brain doesn’t find just one simple meaning for a word; instead it stimulates a veritable trove of knowledge about that word and the many words related to it. The richness of this semantic dimension of reading depends on the riches we have already stored, a fact with important and sometimes devastating developmental implications for our children. Children with a rich repertoire of words and their associations will experience any text or any conversation in ways that are substantively different from children who do not have the same stored words and concepts

Words are vectors; read a lot early and the model sharpens. We bring our entire store of meanings to whatever we read.

2.

The spacing fin.

When Robin Sloan’s latest landed in my inbox I delayed reading it until evening. And I’m glad I did, because when I ran into the section called Dragon Science, my scalp started to tingle.

Mathematician and AI researcher Daniel Murfet traces the embryology of language models during training, showing how structure buds into tissues, organs, and new anatomies. My favorite: a spacing fin, a whole sub-system specialized for counting spaces.

See Murfet’s thread for the “baby serpents” and training maps, and the full paper for the technical story.

3.

The Palindrome is one of those “how is this free?” publications.

Their mathematics for machine learning reads like a roadmap to the core tools you need to poke and prod models. I’d love to hear from a high-school math teacher: how does this arc (linear algebra, calculus, and probability) line up with what’s taught today? We talk a lot about reading and writing in the age of generative AI; how should math change too?

4.

During the summer I’ve been visiting the computer playground. I keep seeing graceful wear and new features ship themselves. The cat sculpture’s tail, not its back, turned out to be the ride; a kid once lay flat and ran the carousel like a hamster wheel.

5.

Claire L. Evans: “There’s no distinction between memory, the memorizer and the act of remembering.” from What can a cell remember?

Maria Stepanova: “Rancière’s most important point is this: in his writing about history, he contrasts ‘document’ and ‘monument’. A ‘document,’ for him, is any record of an event that aims to be exhaustive, to tell history, to make ‘a memory official’. A ‘monument’ is the opposite of ‘document’, in ‘the primary sense of the term’: that which preserves memory through its very being, that which speaks directly, through the fact that it was not intended to speak – the layout of a territory that testifies to the past activity of human beings better than any chronicle of their endeavours; a household object, a piece of fabric, a piece of pottery, a stele, a pattern painted on a chest or a contract between two people we know nothing about…” from Memory of memory.

I love when fiction and non-fiction I’m reading start to rhyme.

6.

On my fall list: Brian Potter’s The Origins of Efficiency. I read with delight his Construction Physics newsletter and the recurring question, where do efficiency gains really come from, works for book lenght work so well. I’m also eyeing Annalee Newitz’s Automatic Noodle, a near-future fiction (with a great website!); and Sophia Jansson’s Kolme saarta – isä, äiti ja minä (out in Finnish and Swedish and no doubt soon in English too).

7.

What makes summer for me is how time goes porous. I’m never more than an eyeblink from being both very young and very old. Great-grandparents, aunts, and cousins collapse into small, sticky summer souls. Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book catches this perfectly. I reread it every year (and read it aloud for the Finnish listeners too!). And this year, there’s the film, too.

8.

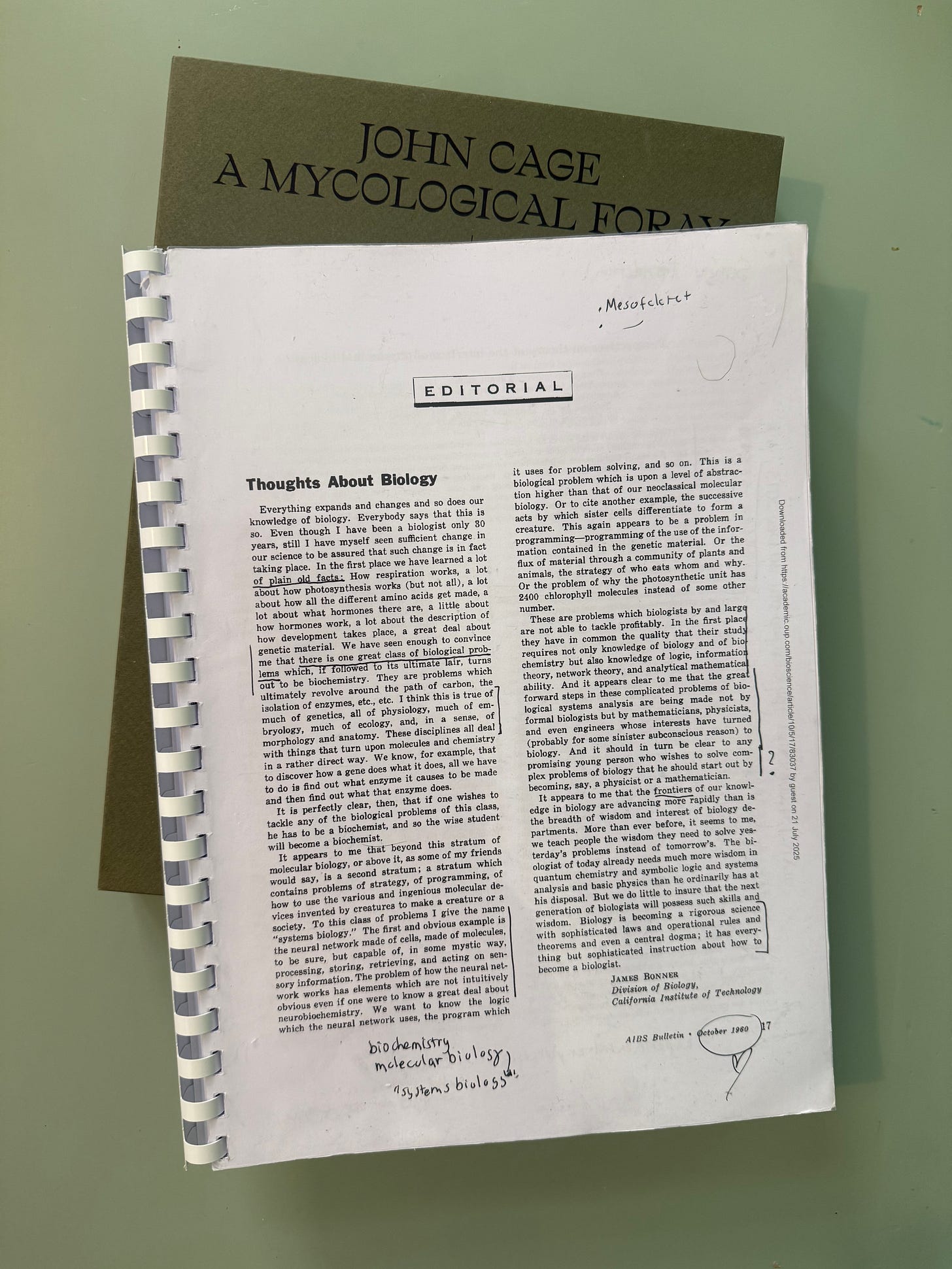

Carrying this little printout everywhere. I understand research better when I print it.

Thoughts About Biology — James Bonner

Perspectives on Theory at the Interface of Physics and Biology — William Bialek

A Mathematician’s View of the Unreasonable Ineffectiveness of Mathematics in Biology — Alexandre Borovik

Is the Cell Really a Machine? — Daniel J. Nicholson

Biology Is More Theoretical Than Physics — Jeremy Gunawardena

A systems biology timeline — Gunawardena Lab

On Being the Right Size — J. B. S. Haldane

Theory in Biology: Figure 1 or Figure 7? — Rob Phillips

Schrödinger’s “What Is Life?” at 75 — Rob Phillips

Molecular “Vitalism” — Marc W. Kirschner; John Gerhart; Timothy J. Mitchison

Can a Biologist Fix a Radio?—Or, What I Learned While Studying Apoptosis — Yuri Lazebnik

Life at low Reynolds number — E. M. Purcell

Thanks for sharing the roadmap of math for machine learning!